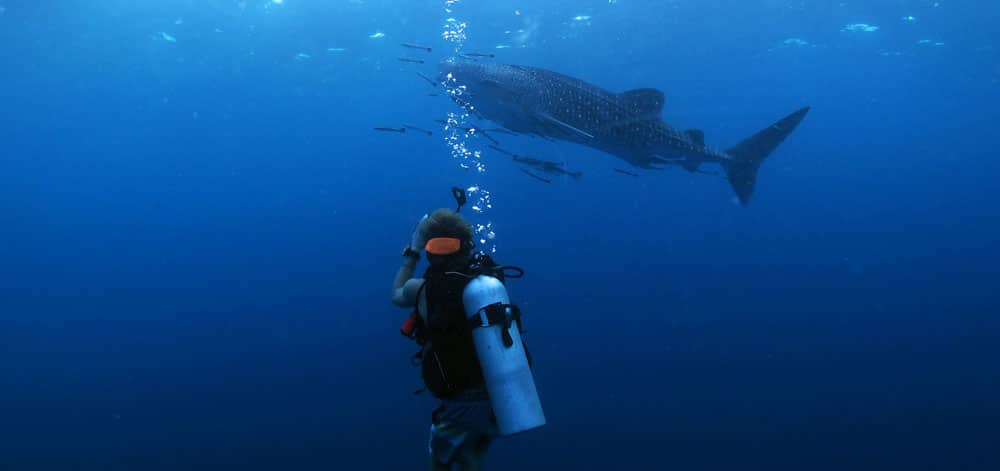

Swimming with the ocean’s largest fish is an experience that changes the lives of any diver lucky enough to have the encounter. Thailand’s whale sharks bring in an untold number of visitors each year, but data shows their populations are declining.

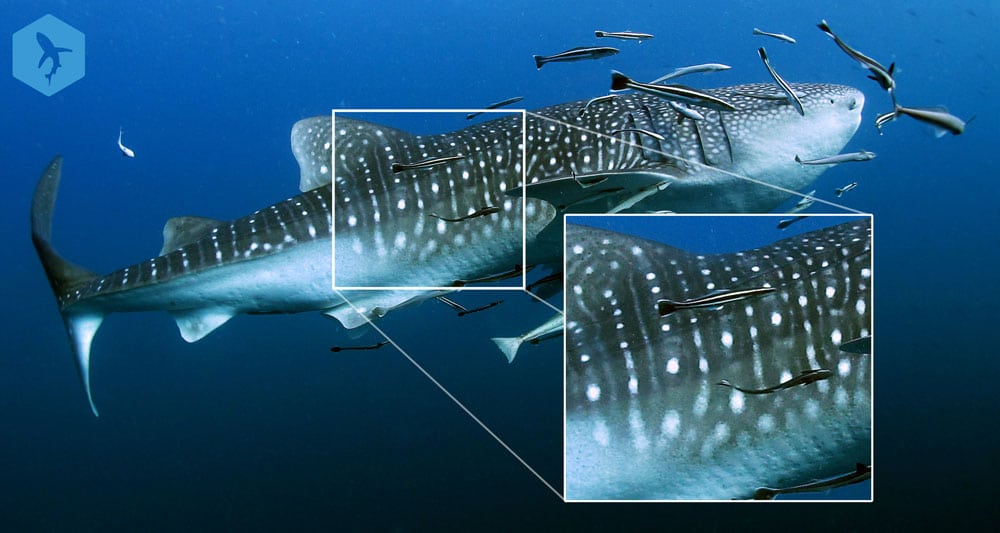

Now, divers and other marine enthusiasts are actively helping professionals to understand and protect these gentle giants through photo databases. Anybody with a camera can capture images of the spot patterns of the whale sharks, which can then be used for identification, much like fingerprints. Groups like Thai Whale Sharks then use that data to track populations and inform local managers and policy-makers.

Whale sharks are found in warm waters worldwide, but their numbers are declining – they’re now classified as endangered. Threats to whale sharks include targeted fishing, accidental fishing (known as bycatch), boat collisions, and entanglement.

To protect these migratory animals, scientists need to understand better where they travel to and from and where they carry out various stages of their reproduction and development. But, collecting such data has historically been difficult and expensive.

That’s why Conservation Diver and partners have recently harnessed the power of citizen science to investigate populations of Thailand’s whale sharks.

Here, we’ll bring you up to speed on citizen science, break down the collected data, and explain how it can help the conservation of whale sharks.

What is citizen science?

Citizen science is the science carried out voluntarily by members of the public. So, how can it be used to monitor whale shark populations?

Just like humans have their own individual fingerprints, whale sharks have their unique spot patterns. This means that photos of whale sharks can be used to assess whale shark numbers and monitor individuals over time.

What’s more, whale sharks are incredibly popular among camera-wielding scuba divers. Cameras that are getting cheaper and better every year. Fortunately, this means that there are heaps of snaps of whale sharks out there.

Members of the public can then upload these whale shark photos to a photo-identification software library. This can tell us key information about the whale shark, like whether it’s male or female or even whether it’s been involved in a boat collision.

Moreover, if multiple photos of the same whale shark are submitted, we can learn even more about whale shark behavior. For instance, it’s possible to determine a whale shark’s annual migration patterns.

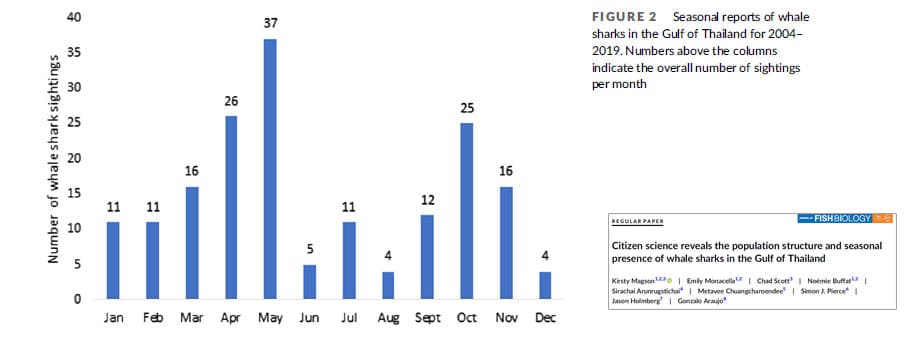

From 2004 to 2019, 247 whale shark sightings were recorded around the three islands of Koh Tao, Koh Samui and Koh Phangan to Koh Tao Whalesharks/Thai Whalesharks. Overall, 178 whale sharks were identified, and some individuals were spotted more than once.

From this data, Kirsty Magson of the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program and Conservation Diver led a team to publish a paper in the Journal of Fish Biology titled “Citizen Science Reveals the Population Structure and Seasonal Presence of Whale Sharks in the Gulf of Thailand.”

What did the study on Thailand’s whale sharks show?

Whale shark size, sex, and scars

All the whale sharks sighted in the area were <6 meters long, making them juveniles. The average total length of whale sharks observed was 3.7 meters.

Sex was only reported for 27% of sightings; however, more female whale sharks were spotted than males (19% were female, and 8% were male).

Scars were reported for 28 individual whale sharks (16%). Fortunately, most of these, such as facial abrasions, were considered minor (79%).

Major scarring included loss of the dorsal fin. These were thought to have been caused by boat collisions and entanglement (for instance, in discarded fishing nets).

Whale shark movements and seasonality

The results highlight a peak in sightings of whale sharks in Thai water during April–May (35% of sightings) and another peak in October and November (23% of sightings).

Some whale sharks were sighted more than once, and one was in another country (Malaysia). The time between the initial sightings and resighting varied from less than one week to more than two years.

Statistical analysis of the data provided further insights. For instance, the whale shark population lost and gained members over time (known as an ‘open population’).

Additionally, some whale sharks showed signs of annual periodicity – this means that whale sharks returned to a site at regular intervals. However, all whale sharks eventually left their site completely.

Whale shark migration routes typically stretch for thousands of kilometers, and the researchers concluded that the monitored sites were used as a pit stop for whale sharks traveling long distances.

How can these data help to protect Thailand’s whale sharks?

Of course, the data described here wasn’t generated in a laboratory and isn’t perfect. For instance, the peak sighting season of April to May coincides with a busy holiday period. This means that a great number of sightings could partly reflect a greater number of tourists with cameras in the area.

Nonetheless, these data provide some key insights that will help to plan further scientific investigations and, ultimately, protective policies.

For instance, most whale shark aggregations are formed mainly of males, but protecting juvenile female sharks is critical for population recovery.

Here, more females than males were sighted (at a 2:1 ratio). Therefore, these data provide further evidence of the need to protect the female-heavy whale shark population that frequents the Gulf of Thailand.

Additionally, 24 of the sighted whale sharks in Thailand were scarred or injured, including missing dorsal fins and rope tied around their tail. Rope often becomes entangled around whale shark tails when ropes are used to drag whale sharks out of nets.

It’s encouraging that whale sharks are being released. However, these observations indicate that part of the rope may remain attached to the shark, causing long-term injury or disadvantaging the individual.

Therefore, these data highlight the need for improved methods of releasing caught whale sharks.

How can I help?

The great news is that anyone can contribute to this research! All you need to do is upload your snaps to the Whaleshark Project (global) or the Thai Whale Sharks Facebook Page (Thailand) after you’ve been swimming with whale sharks.

The database uses technology similar to facial recognition to match the individual to the ones featured in previously submitted photos. If no matches exist, a whole new profile will be generated for that individual.

The website also features a super handy code of conduct for Thailand’s whale shark diving – check it out so you can ensure you act responsibly when encountering one of these majestic creatures.

If you’re keen to dive a little deeper into the study’s findings, you can find the original article here.