A recent publication has shed new light on one of the more diverse and exciting families of corals, Dendrophylliidae. A reorganization of the family is underway using new molecular and imaging techniques and is helping to uncover the evolutionary history of its many species.

The title of this article uses the adjective ‘itinerant,’ which is generally not a word you associate with hard corals, who tend not to wander much. But it fits Dendrophylliidae for multiple reasons. For example, its included genus Heteropsammia, also known as the ‘Walking Dendros,’ which lives on the back of worms and cruises around the sands like kids on dirt bikes. Or, the genus Tubastraea, the only Scleractinian to successfully make it from the Pacific to the Atlantic in the last few million years. As we learn more about the systematics and history of this family, we discover more about the path it has taken to become such an exciting group today.

A New Look at the Family Dendrophylliidae

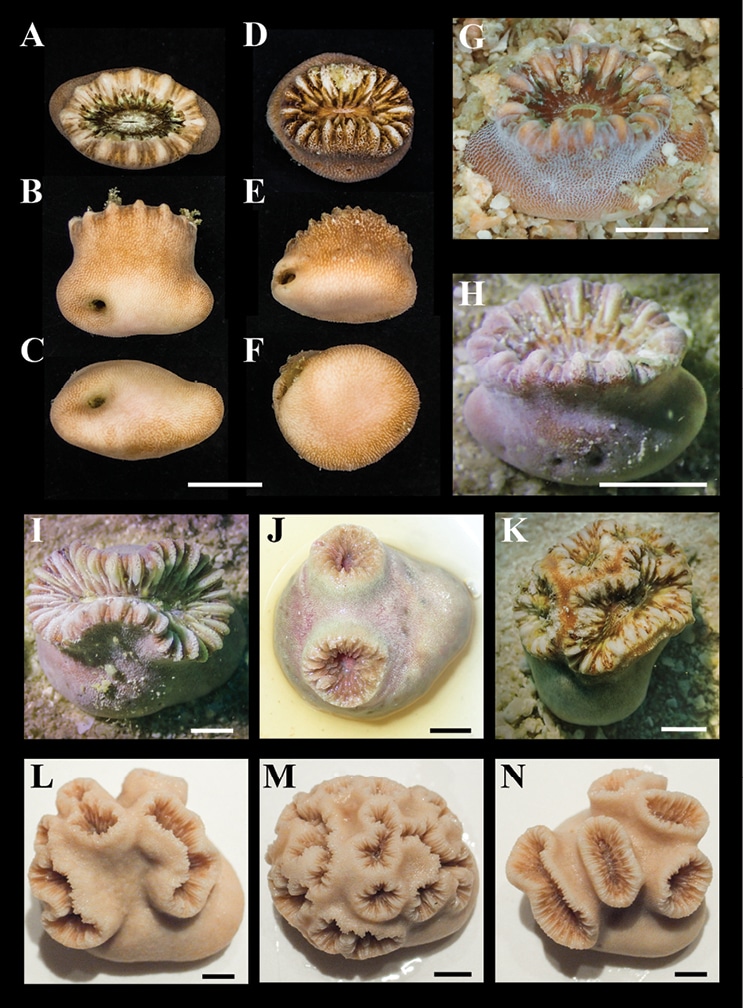

Dendrophylliidae is the third most diverse family of hard corals, with around 183 species. They are an Indo-Pacific group of the order Scleractina but are often non-reef building and azooxanthellate. To date, they have been classified primarily for their apparent morphological features, recently proven in other groups of corals to be quite unreliable and in need of revision.

This last month, Dr. Rahul Mehrotra and several other members and friends of Conservation Diver published a paper in the journal Contributions to Zoology that used DNA testing and high-resolution micro CT scans to propose a new phylogenetic hypothesis of the group. The paper led to many new and interesting findings about an already exciting family of corals, as we will explore here.

Heteropsammia: AKA the “Walking Dendro”

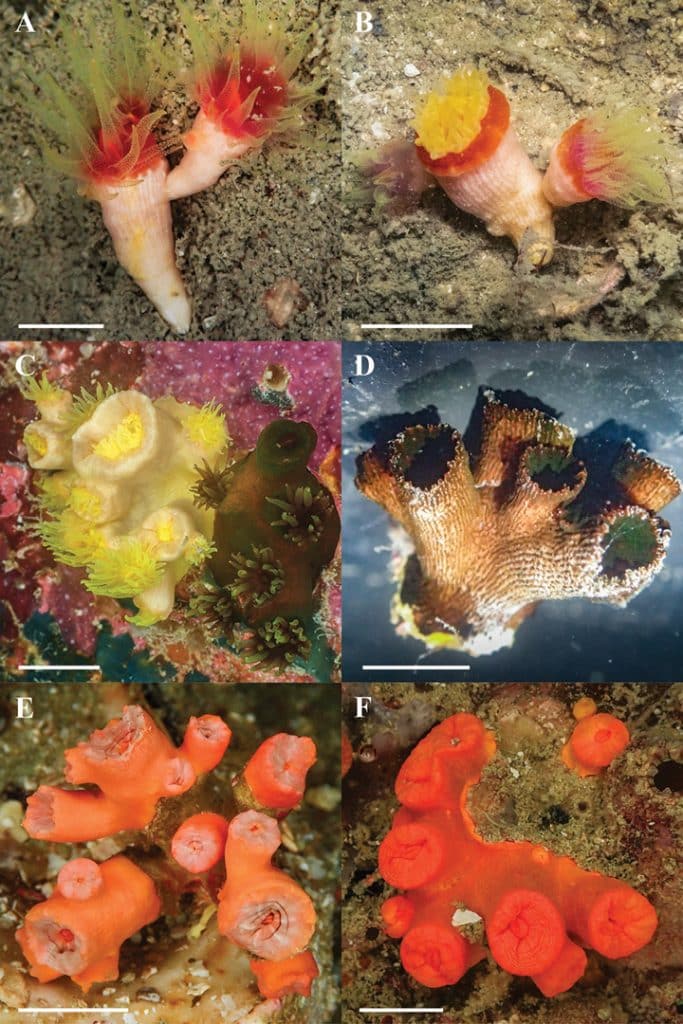

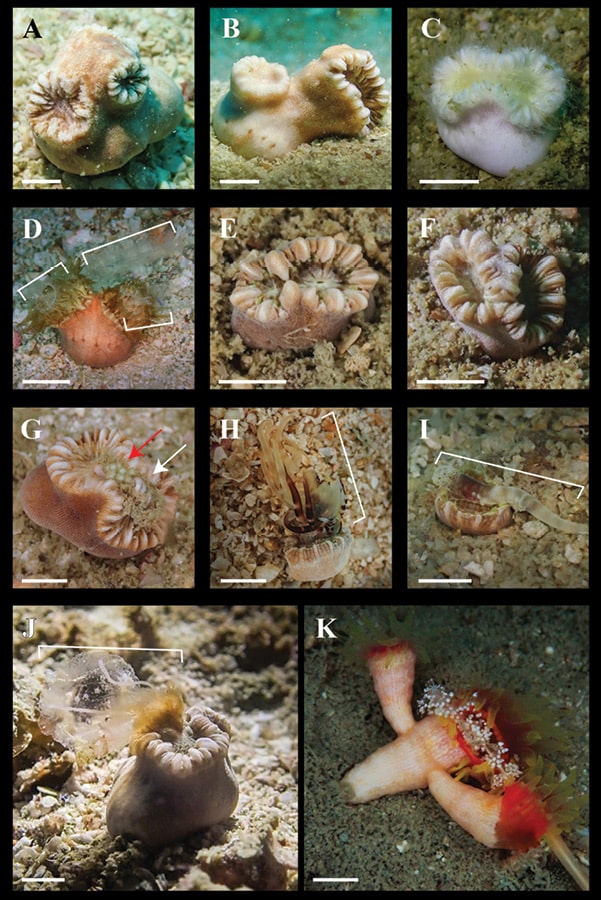

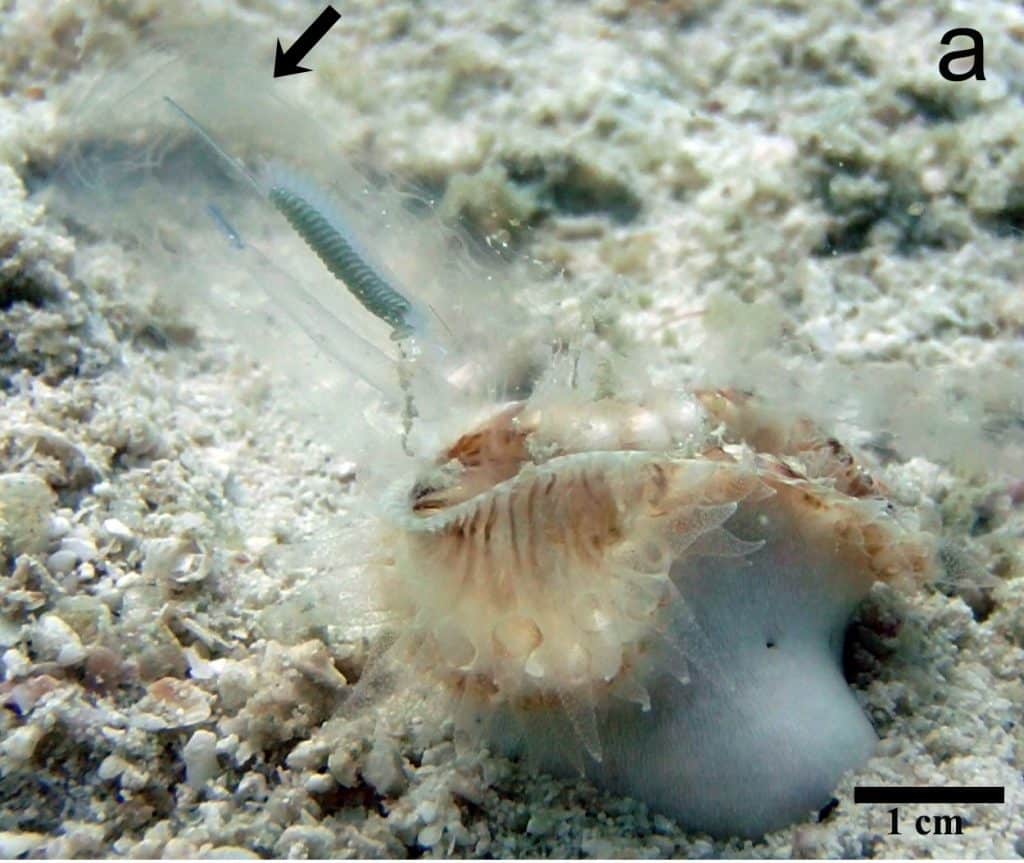

The first coral genera we have to discuss is, of course, Heteropsammia (“Hetero-” from the Greek ἕτερος (héteros) meaning “different” or “other,” and “psammia” from the Greek ψάμμος (psámmos), “sand”). This small, inconspicuous coral forms a symbiosis with both a sipunculid worm (peanut worm) and a parasitic mussel. This worm helps it move around the soft bottom areas it inhabits and avoid being buried by sediment, forming an obligate mutualistic relationship. But how does this relationship even start?

According to Corals of the World, the coral larvae settle on a microgastropod shell out in the silt off the reef. Then, it forms an “obligate commensal relationship” with the worm (Aspidosiphon corallicola) as well as the mussel (Lithophaga lessepsiana), who lives directly above the worm. This is a fascinating observation, but it leaves so many obvious and burning questions completely unanswered. How does this relationship even start? Who links up with whom? Does the coral settle on the worm, or does the worm burrow into the coral? And when does the mussel move in to join this odd couple?

I reached out to Dr. Mehrotra, who explained it further. He said larvae of Heteropsammia settle only on the gastropod shell, and as the coral grows, the shell is left poking out of the side of the juvenile coral. Next, as nobody has confirmed it, he suspects that the worm moves into the shell and takes up residence there. Because the coral larvae form aggregations, it’s likely the worm (which he pointed out is actually Aspidosiphon muelleri) is able to detect and reproduce in a way that facilitates this cycle to occur in mass. He also mentioned that the parasitic mollusk is not always present and was never present in the ones he looked at from the Gulf.

So, still a lot of answered questions there, and hopefully, an investigation that a future student will pick up. It would be fascinating to do spawning and development experiments with both the coral and the worm in our future coral-slug lab on a private Pacific island funded by curious billionaires.

What else was learned about Heteropsammia?

Heteropsammia is no stranger to our team. In 2015 we published how they consumed sea salps much larger than themselves, not with their tentacles, but instead by opening their mouth really wide and using their digestive filaments (new horror movie idea, anyone?). Then, in 2019, we included them in our feeding trial paper investigating heterotrophy in corals and their ability to eat sea slugs (this time having some manners and using their tentacles).

This new paper not only helps to reorganize the species within Heteropsammia more accurately, it also made several new mind-blowing observations. First, in addition to hosting the sipunculid, one coral also was found to host a comfy little hermit crab in the worm’s burrow (a first for Koh Tao), and another was found to be hosting a beautiful but parasitic epitoniid snail (think Wentletrap). It also added several new items to the ‘list of things we have seen them eat,’ including more sea slugs (rest in peace Costasiella), an anemone, and even a whole jellyfish. Wow.

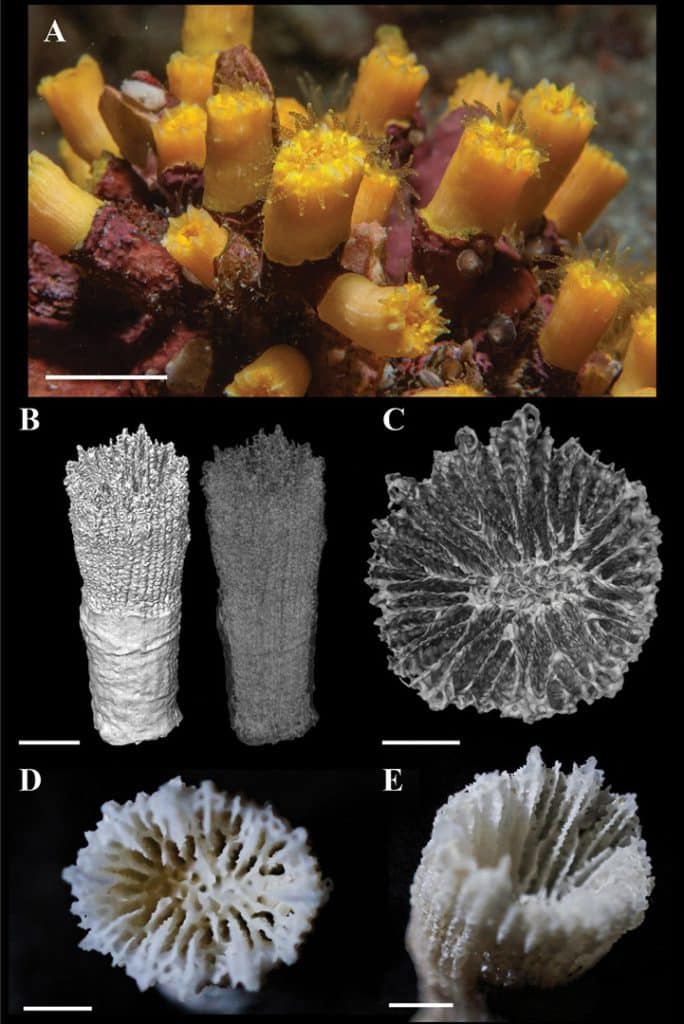

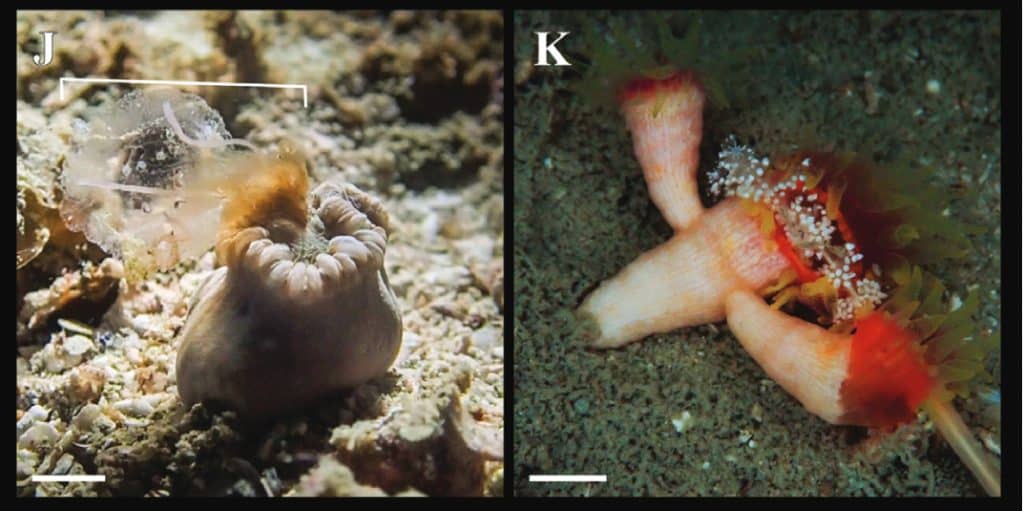

Tubastrea: the world traveler

Tubastraea (“Tuba” from the Latin word for “tube” and “Astrea” from the Latinized form of the Greek “Astraea,” referring to star-like shapes) are known for their bright colors and huge corallites. They are conspicuous corals found throughout the Indo-Pacific, often in areas with poor light (overhangs, caves, turbid waters, etc.). They can grow to incredible sizes, but their azooxanthellate nature means their skeleton is thin and brittle, often not contributing to reef growth.

Feeling a bit of wanderlust, two species of Tubastraea (T. coccinea and T. tagusensis) stowed away in the bilge water of a boat traveling through the Panama Canal in the early 1980s. Since then, they have successfully colonized this new ocean, setting up along more than 3,500 km of coastline in the Atlantic and Caribbean. According to genetic analysis, the word is out, and several more migrations have occurred since the first pioneers made their way over. They now hold the record as the only Scleractinian with populations in both oceans.

As cosmopolitan as they are, there is still so much we don’t know about them and their habits. This new paper saw them doing strange things (while confirming or reclassifying many species). First, a colony was found cooperatively eating a sea pen (Pennatulacean), with two coral polyps holding down the sea pen while the third ate it. This is the first recorded observation of an Anthozoan eating another Anthozoan. The brutal gang behavior of Tubastrea must now be well known in the area, as the team did not find any parasites, predators, symbionts, or epibionts on the corals they observed.

Other findings from the ‘muck.’

Besides thoroughly examining the family Dendrophylliidae in the Gulf of Thailand, the paper highlights the overlooked soft-sediment, or muck, habitats. Recreational diving in the region is primarily confined to the near-shore fringing reefs or the scattered submerged pinnacles dotting the Gulf. As such, most of the attention has been placed there, and in the face of climate change, this is not unwarranted.

But, a largely unexplored and overlooked treasure trove of biodiversity exists in the muddy plains that comprise much of this ancient submerged basin. New and exciting organisms, relationships, feeding habits, and survival mechanisms await observation, pondering, and learning.

Based on observations from around the region, the team predicts that two more genera of Dendrophyllids are waiting to be found in the area. It is hoped that bringing attention to the natural riches of these areas will increase public demand for protection and help aid in their continued survival.

Please check out the full paper, Biodiversity, ecology, and taxonomy of sediment-dwelling Dendrophylliidae (Anthozoa, Scleractinia) in the Gulf of Thailand, by Rahul Mehrotra, Suchana Chavanich, Coline Monchanin, Suthep Jualaong, & Bert W. Hoeksema.