Proactive and reactive ecosystem restoration are two new terms that more accurately define what is actually happening in the real world. They are replacing the old terms of passive and active ecosystem restoration. The two modes were broadly defined in terms of where the human energy and resources were put in the hopes of bringing back ecosystem health and function.

In passive restoration, the energy was put into stopping the threat and letting the ecosystem recover independently. In active restoration, our energy and resources assisted or facilitated the ecosystem’s recovery more directly. These terms were always a bit ambiguous and poorly conveyed the nuance and complexity of the actions being performed by managers.

In a new paper by Hein et al., 2021, the authors discuss this issue and propose using new terms to describe these two restoration branches as they pertain to coral reefs. They introduce the term ‘proactive’ to replace passive, and ‘reactive’ to replace active restoration. These terms more accurately describe the actions being taken and may make communicating the details of these projects more precise and relatable. We at Conservation Diver will be switching up our terminology in support of this, and here is why we think you should too.

Passive and Active Coral Restoration

For decades, the prevailing opinion and policy of reef managers were that protection is always preferred over restoration. By stopping the threats to the ecosystem, the flora and fauna would rebound independently without further human intervention. From this came the term ‘passive restoration,’ meaning that no time, energy or resources were put into the ecosystem to return its health, diversity and function.

However, this term implies that nothing is being done when in fact stopping the threat is anything except “passive.”

For example, Tanote Bay on the island of Koh Tao, Thailand, was one of the more beautiful and vibrant reefs in the entire region. In 2006, the municipal government constructed a large reservoir above the bay to address the island’s unstable freshwater resources.

This was accomplished through massive deforestation, road cutting, and digging on the highest peak in the bay’s watershed. By 2008, millions of tons of sand and clay had been washed into the bay, burying the reef under 1-2 meters of sediment. The coral reef was literally gone, and the water quality was extremely poor as more sediment loaded the area with each rain.

In 2008, we worked with the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program, the Save Koh Tao Community Group, and many community volunteers to ‘passively’ restore the bay by stopping erosion and sedimentation.

This included planting hundreds of thousands of Vetiver grass tillers and trees; constructing over a hundred check dams, and installing hundreds of erosion control logs and blankets: all of which took more than three years. In our minds, it was anything except passive, as the word is used in everyday language. However, since we were not working in the coral reef itself, that was how it was defined.

In the same way, the word ‘active restoration’ never really encompassed what managers were doing or moving towards in their techniques and methods. As Hein et al. point out: in the past, restoration was thought of as the act of bringing the ecosystem back to its historical state. However, bringing ecosystems back to their historical state will not be possible in the face of the increased effects of climate change.

Instead, the focus must shift from maintaining historical species to maintaining the “key ecosystem processes, functions, and services through the next few decades of climate change.”

Proactive and Reactive Ecosystem Restoration

The authors (Hein et al., 2021) propose the two new terms as a way to clarify the actions being done and the intent behind them in the context of a rapidly changing planet.

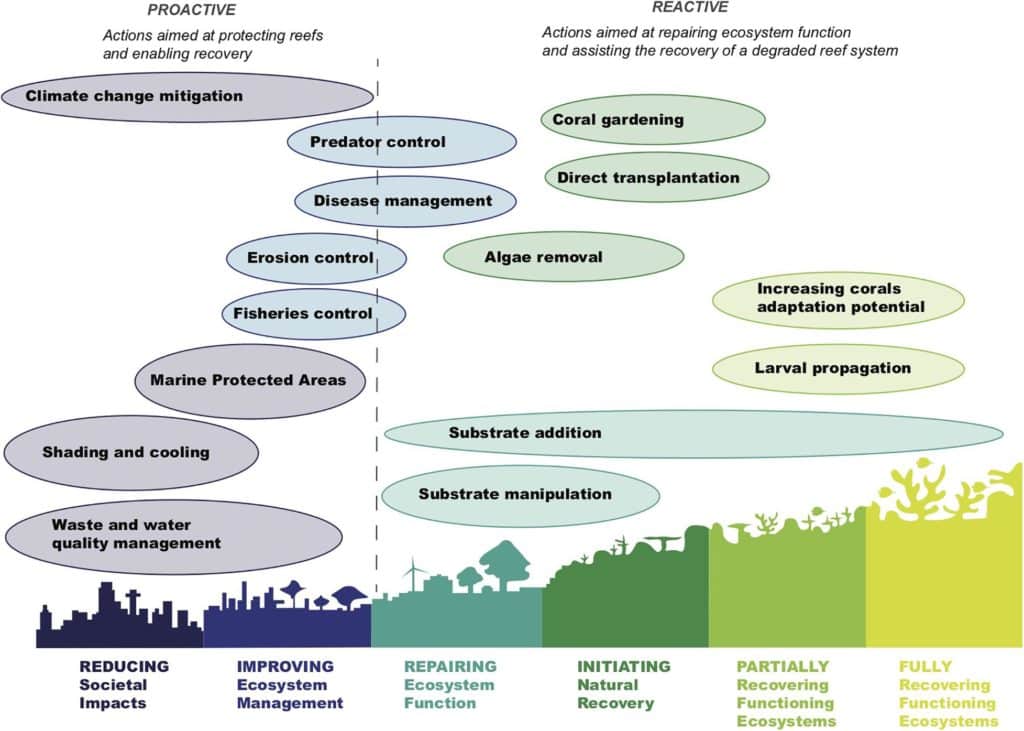

Proactive restoration would thus refer to any act or initiative aimed at “protecting and enabling recovery.” These proactive measures then go on to support the reactive measures “aimed at repairing ecosystem function and assisting the recovery of a degraded reef system, should it not be able to recover on its own.”

With this new, more accurate terminology, the things we do to protect the ecosystem (such as erosion control, wastewater treatment, and mooring buoy installations) are considered proactive measures. These are things done primarily on adjacent ecosystems to help facilitate recovery within the target ecosystem.

In some cases, like when there is still available structure and high larval supply, this can be all that is required to return the ecosystem services and function. And even in situations where those factors are not present, it is still the prerequisite for most successful reactive projects down the line.

Reactive projects in coral restoration would include coral gardening, artificial reefs, larval culturing, and all the other projects reef managers implement as part of a successful holistic program. These are the actions taken to increase the health, abundance, and diversity of key reef species or improve their resilience and help them adapt to changing conditions. The authors of the report developed this graphic to help visualize the actions taken under each mode of coral restoration:

The coral restoration industry is still in its infancy but is one that is becoming more urgently necessary with reefs around the world in rapid decline.

While we work to solve the issues leading to climate change, we must be proactive and reactive in our efforts to preserve ecosystem value and function. These new terms help to show not only the effort and planning that has to go into what was once called passive restoration but also open up what was active restoration to include the work being done to build resilience and assist in the adaptation of corals through breeding programs. This is only one minor point that this vital report brought up, so stay tuned as we dive deeper into its recommendations and implications.