Understanding Corallivorous Drupella Snails

Although outbreaks of corallivorous Drupella snails have been increasing across the Indo-Pacific since the 1980s, still very little is known about their reproductive ecology. These tiny snails can occur in great abundance and can contribute to reef decline by lowering the total abundance of living coral and changing the population structure of reef communities.

Tracking these Coral Predators

Conservation Diver has been focusing on Drupellas for some time, with our first observation of the snails shifting their preferred food sources following the global mass coral bleaching event of 2010. Since then, our partners at the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program have collected more than 179,740 Drupella snails from around the island of Koh Tao, with 76% coming from a single bay.

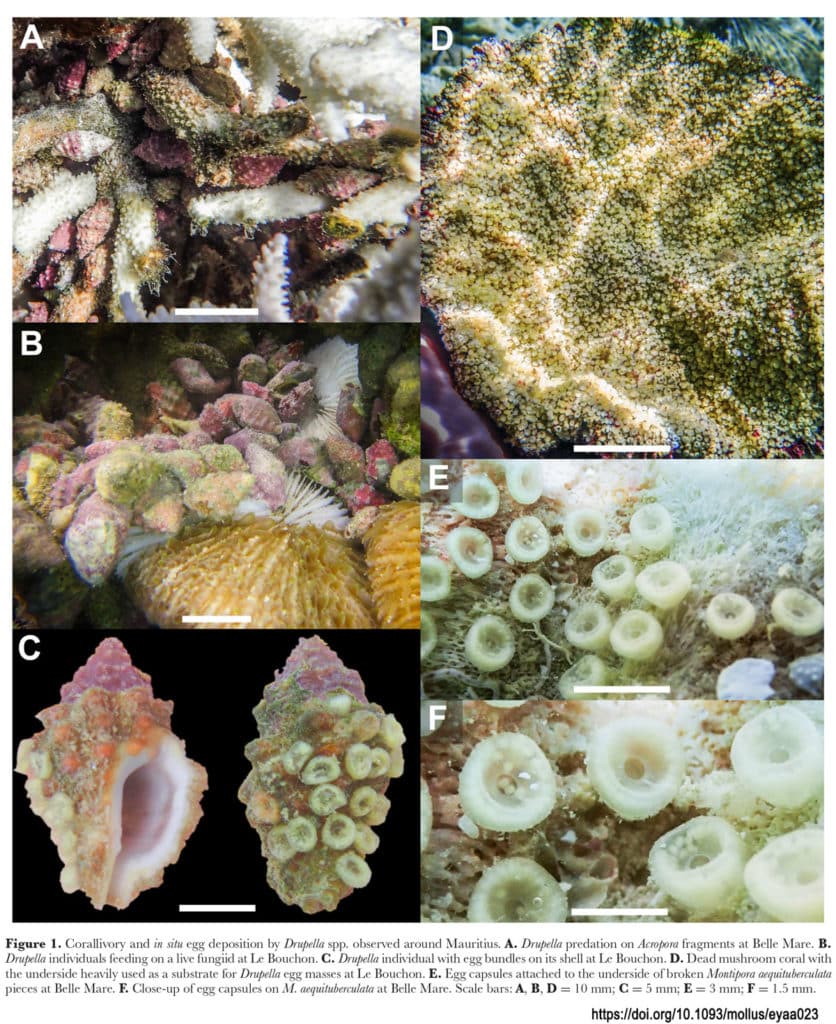

In 2019, a team of our Conservation Diver Trainers traveled to Mauritius for a collaborative research expedition with the University of Mauritius. They were pleased to apply their Drupella snail knowledge to the local reefs and assist published Drupella snail researcher Deepeeka Kaullysing, in recording observations from the area. During their biodiversity surveys, primarily focused on heterobranchs, they noticed a significant deposition of egg masses under mushroom corals in the vicinity of a large Drupella aggregation. Upon closer inspection, they realized they were looking at the largest concentration of Drupella egg clusters ever recorded.

Although the first outbreak of Drupella snails was recorded in the early 1980s, much of what we understand about their life history is derived from similar organisms. Very few publications detail observations of the egg or larval stage of these predators, which is vital to know to mitigate the damage caused by over-populations or outbreaks.

Understanding Drupella Lifecycles

The first recorded Drupella egg deposition was published by Sam et al. in 2016 in an aquarium. This was followed quickly by the first in situ observation in 2017 by Scott et al. and was also the first record of egg deposition on the underside of Fungiidae corals.

The recent Kaullysing et al. (2020) publication is the first record of Drupella egg deposition in Mauritius and the Western Indian Ocean. Additionally, this is the first record of in situ egg deposition on corals other than Fungia. This time, eggs were observed on Fungia, Montipora, and the shell of another Drupella snail.

Furthermore, it represents the highest abundance of corallivorous Drupella eggs ever observed, with 5,020 egg bundles on a single coral (each bundle contained approximately 96 embryos).

Observations such as these are vital to the understanding of the ecology and life history of these cryptic species. Only 40 years ago, they were essentially unheard of, yet today they are seen as one of the Indo-Pacific's significant problematic coral predators.

Stopping Outbreaks of Drupella

To halt outbreaks and mitigate their damage, reef managers must understand the details of their life history. By targeting benthic egg cases for removal rather than the adults, much time and resources could be saved.

The program on Koh Tao has been working for a decade to remove nearly 180,000 adult snails, whereas removing just the observed corals in Mauritius could potentially prevent the dispersal of 1.6 million embryos (4 corals x 5,000 egg bundles each x 80 embryos per egg bundle).

This is a very important publication for the advancement of this field and surely will be one of the stones placed on the path to better understanding and management guidelines for these pervasive coral predators. We wish our sincerest gratitude and congratulations to all of the authors, but especially those on the Conservation Diver team; Rahul Mehrotra, Spencer Arnold, Alyssa Allchurch, and Elouise Haskin.

Be sure to check out the paper here

A New Record of Heliopora Coral

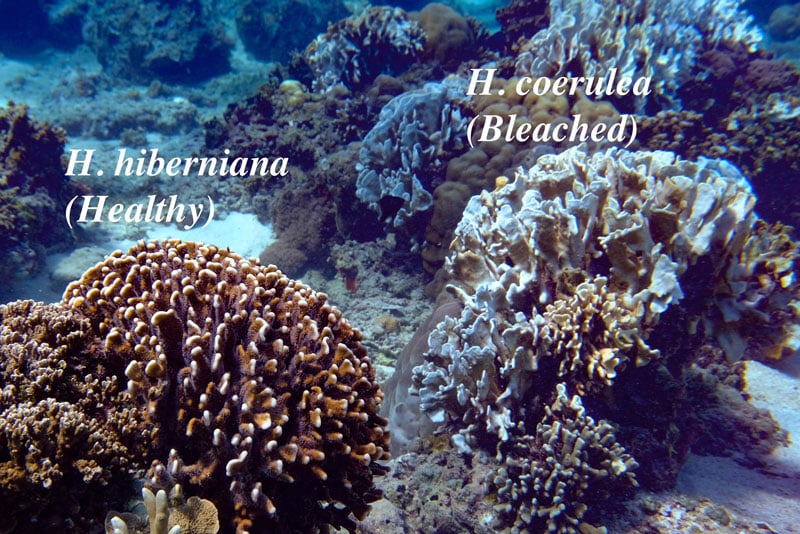

Until recently, it was thought that the genus Heliopora was monotypic, with the only species described as Heliopora coerulea. However, that is quickly changing, and the Conservation Diver team is helping to increase records around the Indo-Pacific. Our finding represents the second hermatypic octocoral we have discovered in previously unknown locations, after Pau Urgell found the very rare coral Nanipora on Koh Tao in 2014.

A Reef-Building Soft Coral

Heliopora is an octocoral (mostly soft, non-reef building) however it is hermatypic, meaning that it is a reef builder. This genus is unique in that the skeleton has a blue coloration derived from the iron salts in its fibrous aragonite matrix.

This species can be traced back more than 120 million years to the Cretaceous Era and has remained mostly unchanged since. It was only in 2018 that the first records of a second species of Heliopora (H. hiberniana) was described, and only from 3 locations in Western Australia. But even then, it was hypothesized that this cryptic species could be more widespread.

Whilst working on coral nurseries in the Maldives, Conservation Diver Board Member and head of Conservation Diver Indonesia, Leon Haines noticed a Heliopora colony that did not match any seen in the guide books.

After a quick online search, he stumbled upon the newly described species and contacted the scientists with a photo to confirm his suspicions. Indeed, it was a colony of H. hiberniana over 6000 km from the area it was originally described to science!

After his time in the Maldives, Leon returned to Indonesia where he subsequently noticed H. hiberniana to actually be one of the most common reef-building corals in the Gili Islands! After working with other researchers, he published the first record of H. hiberniana outside of Australia, this time both in the Baa Atoll, Maldives, and the Gili Islands of Indonesia.

Heliopora on Future Reefs

This is a significant find, as in the future, non-scleractinian hermatypic corals may be forced to play a more prominent role in sustaining the structure of coral reefs around the globe.

These octocorals seem to be less susceptible to warming climates and coral bleaching events and may provide an alternative structure to the historic hard coral species which built them. These records are also vital to tracking the effects of climate change as the historic home ranges of various species are altered due to changing ocean conditions and can help us to predict where conservation and protection efforts will be the most effective.

We extend our sincerest congratulations to Leon for this publication and are excited to see how we can contribute to the development of the understanding of this species in the future.