When we perform coral restoration activities, the goal is to not only increase the amount of living coral, but to enrich the entire ecosystem, including the fish communities. Restoration programs tend to focus on bringing back living coral, under the idea that by bringing back the foundation of the ecosystem, the rest of the reef organisms will follow. But is that truly the case?

A recent publication headed by Dr. Margaux Hein investigated whether long-term coral restoration programs did in fact bring back fish communities, and the results were not as significant as some restoration practitioners might expect. The study, titled “Effects of coral restoration on fish communities: snapshots of long‐term, multi‐regional responses and implications for practice,” was published in April in the Journal of Restoration Ecology. It analyzed four coral restoration sites, all of which had been ongoing for 8 years or longer, two from the Caribbean and 2 from the Indo-Pacific. The studies where completed in the same locations as her publication on the effectiveness of long-term coral restoration, and builds upon the lessons learned from that study.

The study assumed, like most of the coral restoration industry, that efforts to bring back corals and structure would also attract a wide range of reef fishes, thereby restoring the function and value of the ecosystem. Not only are the corals essential for the survival of the fishes, but the fishes (especially the herbivores and detritivores ones) help to maintain the dominance of corals on the reef over macroalgae. In general, more fish biomass is thought to represent a healthier ecosystem, and also leads to more value for local economies through tourism and fisheries. So, reef restoration efforts should be concerned with the abundance and biodiversity of fish communities when evaluating the effectiveness of their efforts.

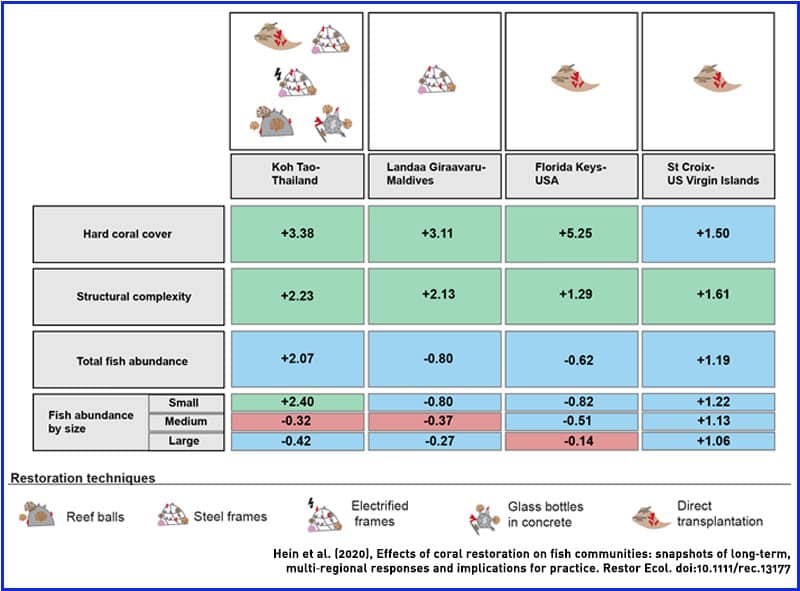

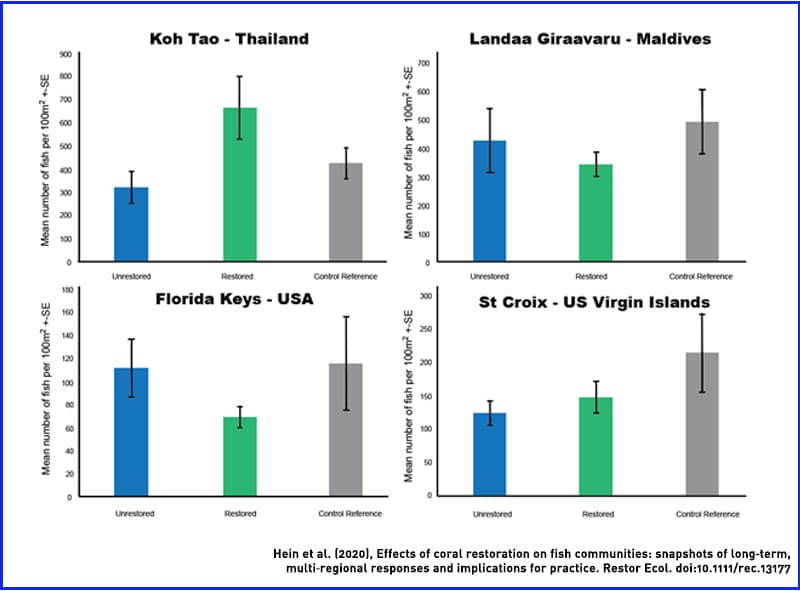

In Dr. Hein’s study, she looked to see which of the various restoration methodologies most positively affected fish communities, and hypothesized that locations which had the highest structural complexity of corals would also have the highest abundance and diversity of fishes. She and her team carried out transect surveys for fish at four locations around the globe, and looked at three site types for each location; restored reefs, unrestored reefs (adjacent to and degraded to a similar extent as the restored reefs, but with no actions being implemented), and control reefs (those with little relative degradation and no restoration, but similar in composition). Each location had three replicates per site type, for a total of at least nine replicates per location studied. They categorized reef fishes into three groups by size (small, medium, and large), and by genera.

Although in the last study they found significant differences between the coral communities at each location, results regarding the fish communities where far less significant. In fact, only one site, the one at Koh Tao, operated by our partners at the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program, showed any increase in fish biomass or diversity, and it was not statistically significant. At Koh Tao, the restored sites had the most fish, a 2-fold increase, but only among the smaller fishes, and only of the damsel fish family. At other locations, the fish abundance did not vary greatly between sites, and in the Caribbean was actually highest at the control sites (again, not significantly). When it came to medium and large fish, they were generally lower in the restored sites than the unrestored or control sites.

The study went on to point out that, on Koh Tao, a variety of methods where utilized, including transplanting corals to the natural reef as well as to artificial substrates, whereas at all the other locations only one strategy was utilized. Thus, interning again that taking a holistic approach to restoration may be preferred over focusing all time and resources to just one method, as in the other programs assessed. By increasing the structural diversity and available habitat on the reef through the creation of artificial reef structures while also increasing the amount of living coral on natural reef areas more consistent benefits are realized.

In the end, the study did not find significant differences in fish community biomass and diversity, contrary to the original hypothesis. The authors discussed possible reasons for this, and gave recommendations to future studies and restoration programs for improvement. The study concluded that:

“Coral restoration efforts aiming at increasing fish abundance and diversity on degraded reefs should strive to substantially increase both coral cover and structural complexity by maximizing coral diversity, and use a diverse set of artificial transplantation substrata where possible. Importantly, there is likely no “one size fits all” approach to restoration when it comes to maximizing the response of fish communities. Rather, to realize such a goal requires a location-specific understanding of the community, that will need to be incorporated at all stages of the design of the restoration efforts, from site-selection, planting design and monitoring regime. “

We at Conservation Diver wanted to know a little bit more about what Dr. Hein felt was the most vital aspects to coral restoration, as she has published many studies on the various aspects of it, and has visited many reef restoration programs around the world, here is what she said:

Q1: Your study found that there was little in the way of significant improvements at the restored sites at all of the locations studied, despite the hypothesis to the opposite. What do you think are the main things that restoration is missing that would improve fish abundance and biodiversity?

The limited response of fish to restoration I observed might very well be due to my study-design and the fact that I only got a “snapshot” of what fish population looked like at each location, with a one-off survey. Fish move (haha), so properly documenting their response to restoration would require repeated surveys from the very beginning of the restoration efforts. Still, I think there are ways in which coral restoration programs could be better designed to improve fish abundance and diversity:

1. Site selection should be based on local knowledge of fish communities’ dynamics and connectivity

2. Restoration designs should maximize 3-dimensional structural complexity

3. Restoration designs should improve coral diversity

Q2: Since you have dived at many different artificial reefs/restoration projects around the globe, what technique do you think works best to attract a diverse population of fishes?

I think the key is habitat structural complexity and diversity. Fish are attracted to places for food and shelter, and complex structures provides refuges of different sizes as well as diverse feeding surfaces. Maximizing habitat complexity can be done by adding artificial structures and maximizing coral diversity.

Then obviously, site selection is very important, making sure that the restored area is somehow connected to healthy fish populations – the ideal scenario being for the restored sites to be within no-take marine protected areas. The more the restoration efforts can be integrated within resilience-based management, the better success we’re likely to see in the long-term.

Q3: Which fishes do you think are most important to attempt to attract when planning a restoration project?

That’s a tricky question- I think it all depends on the initial goals of the project. If initial goals are focused on enhancing fish nursery habitat for local fishermen, then it’s important to specifically look at the response of fish species that are important for these fisheries. These may have specific food and shelter requirements that the restoration efforts can accommodate. If initial goals are focused on restoring ecological function and resilience, then we need to look at the response of functionally important fish species and restoring key ecological processes such as herbivory. These goals are not necessarily mutually exclusive, but better defining goals is important when planning and designing restoration efforts.

Q4: You have now written several papers and book chapters on coral reef restoration, what are the main lessons you have learned, that you think the industry needs to heed in order to be more successful in the future?

I would say that the most important lesson I have learned is that there is a lot more to coral restoration than growing and planting corals. In particular, it can be a useful educational tool that encourages tangible behavioral changes and improves the social resilience of local communities as well as the ecological resilience of the reef. But there is no “one size fits all” approach. To be successful it needs to be carefully planned and designed against specific long-term goals, integrate stakeholder engagement, and most importantly be integrated within a greater reef management plan that act on stressors such as MPAs, water quality and predator control, and the obvious elephant in the room: climate change.

We want to wish our sincerest congratulations to Dr. Margaux Hein for this valuable and encouraging study, and also a big congratulations to her co-author, and our board member Eloise “Elle” Haskin, on her first scientific publication! Surely many more are to come.

Also be sure to check out what Dr. Hein is currently working on by checking out her marine restoration and consultancy company website.