How effective are our coral restoration techniques?

As coral restoration techniques becomes more mainstream, it is important that the industry takes every measure to ensure that the techniques used are valid and effective. Today there are many groups out there doing various forms of corals restoration, and the importance of their work is becoming more and more apparent as recent reports have found that more than 50% of the world’s coral reefs are already gone, and the rest are not doing well. Coral bleaching events are becoming much more frequent and severe, and so are coral disease outbreaks. No reefs are safe from these global effects, both those in marine protected areas and those without strict protections are being lost at similar rates, which is why we no longer have the luxury to put our efforts into only preservation without also focusing on restoration.

But are the coral restoration techniques being used by various groups working? Its hard to say, the database for coral restoration developed earlier this year found that 60% of projects do not monitor their work for more than 18 months, with many not doing any post-transplant monitoring. How can any coral restoration program claim success if they don’t have long-term monitoring? Just growing corals in a nursery is not restoring the reefs, in order for the project to be a success it must improve the long-term resilience of the reefs, ensuring biodiversity and the corals ability to withstand and adapt to various chronic and acute stresses.

A recent publication led by Dr. Margaux Hein of James Cook University, seeks to evaluate the long-term impact of 4 different coral restoration programs that have been in action for more than 10 years, two from the Indo-Pacific and two from the Atlantic. In her paper, titled “Coral Restoration Effectiveness: Multiregional Snapshots of the Long-Term Responses of Coral Assemblages to Restoration,” she evaluates the programs based on 5 factors: (1) Benthic Cover, (2) Structural Complexity, (3) Coral Health, (4) Generic Richness, and (5) Juvenile Recruitment; based on surveys of both the restoration sites and control sites. Of the 4 locations studied, only our program on Koh Tao showed improvement in all 5 factors, indicating that our techniques are the only ones which not only increase the amount of coral on the reef, but also preserve the structure and function of the reef while enriching its resilience to future threats.

(1) Benthic cover

The study found that coral cover was more than twice as high

in the restored reefs then the unrestored ones in three out of the 4 locations,

in the fourth, coral coverage was still higher, but not significantly. So all the

programs are increasing coral coverage through their efforts, but the effects

on reef resilience are more nuanced, as we will see in the next few sections.

(2) Structural complexity

All four sites showed higher structural complexity on the restored reefs than the unrestored ones, however only 1 showed structural complexity higher than the control reefs, our program. The structural complexity of our restored reefs was twice that of the unrestored ones, and slightly higher than the control reefs. This is probably due to our widespread use of artificial reefs as a way to increase the available habitat for corals and other reefs organisms in addition to our work transplanting corals back to the natural reef areas. By taking a holistic approach in our coral restoration techniques we have been able to not only bring back corals, but continue to improve the available habitats on our reefs.

(3) Number of coral juveniles

The two sites in the Atlantic could not be analyzed for this parameter as too few juveniles were found, however, for the Indo-Pacific sites only ours showed an increase in coral juveniles, with a 3 fold increase between the restored and control sites, with no juvenile corals found in the unrestored sites. These were primarily on our concrete artificial reef structures, but may also be because of our coral spawning and larval culturing programs.

(4) Coral generic richness

Increases in coral species richness only occurred in our restoration sites on Koh Tao. In the two Atlantic programs, coral diversity was about the same, and in the other Indo-Pacific project it was actually lower in the restored sites than the unrestored or control ones. This is probably the biggest ‘win’ for our coral restoration techniques, as it has been what our program has focused on since the beginning. Instead of asexually reproducing the fastest growing corals on the reef like many programs, our aim as always been to create feedstocks for restoration by collecting ‘corals of opportunity’ over a wide spatial and temporal scale, and these results justify that philosophy, and further adds credibility to our arguments against coral fragging.

(5) Coral Health

Again, we were the only program to show significant differences

in coral health between the unrestored sites and the restored ones. At our

reefs, the restored reefs had a 4-fold lower incidence of problems with coral

health over the unrestored reefs, and our restored reefs were also slightly

healthier than the control reefs. In the Atlantic programs, where asexual propagation

is widely utilized, coral health was worse in the restored areas than they

control or unrestored reefs. Implying that the effects of reduced genetic diversity

resulting from asexual cloning have real, long-term negative impacts on reef resilience.

This is the first study of its kind, to evaluate and compare various long-term coral restoration techniques based not just on how many corals they have planted, but what the long-term implications of their work is on the sustainability and survival of the reefs. We couldn’t be more proud of our program, as we have worked so hard over so many years just trying to do something good. To have this study justify our philosophies, methods, and techniques is one of the greatest outcomes we could ever hope for, after of course seeing our reefs thrive once again. This is a great honor for us, and give us even more motivation to continue our work. We must also give a huge thanks to the thousands of people who have helped us along the way, primarily the staff, students, and interns at the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program on Koh Tao.

The First Global Coral Restoration Database

"Protection is always preferred over restoration."

That has been the general consensus of the scientific community regarding coral reefs for most of the last five decades. However, in our rapidly changing world, corals reefs are being depleted at an alarming rate, and thus far protective efforts have proven to be insufficient at stopping what could be a global collapse of these important ecosystems. More and more, reef managers have been implementing and developing restoration techniques in what can sometimes only be described as a last-ditch effort to preserve their local resources. There has, however, historically been a major disconnect between their efforts and the work being done by scientists and academics. This is all starting to change with the recent development of the world’s first coral restoration database, as described in a recent publication titled “Coral restoration – A systematic review of current methods, successes, failures and future directions.”

This collaborative effort aims to collect all of the disconnected works being done by universities, NGO’s, local managers, for-profit restoration companies, and individuals around the globe into a cohesive dataset that can be analyzed and used to direct future efforts. This is a major undertaking, especially since there has never been much incentive for reef mangers to publish their work in scientific journals, nor has there been much incentive for for-profit groups and those receiving funding to publish their negative results, or failures. This has led to an incalculable amount of time and resources being wasted as folks attempt to figure things out for themselves, or reinvent the wheel, and often also repeating the same mistakes. In some cases, those working to preserve the environment may also be contributing to its decline.

One of the major problems plaguing coral restoration work can be traced back to a lack of long-term monitoring, which is one of the major criticisms that this paper has brought up. According to the author’s analysis, about 60% of projects reported monitoring for no more than 18 months, with many monitoring for less than one year. However, as anybody in the field knows, pretty much anybody can get corals to grow when conditions are good, but all that work can be for nothing when the next bleaching event or disease outbreak is experienced. So, reports of greater than 70% survival after 1 year may sound great for those projects looking to get more funding, but are they truly restoring the ecosystem?

The authors of the study identified 3 main issues that currently are plaguing the coral restoration industry: “1) a lack of clear and achievable objectives, 2) a lack of appropriate and standardized monitoring and reporting and, 3) poorly designed projects in relation to stated objectives. This new database will hopefully help lead to better understanding and a more focused approach to restoration that actually addresses the issues at hand, and achieves the objectives that have been set out.”

The future potential of the database and the work being done by the project authors can help to legitimize the industry, address the lack of scientific knowledge among some local managers, and help to promote the sharing of new techniques as well as the knowledge on what techniques do not work.

We at Conservation Diver have been attempting to build a network of coral reef managers that are well trained in the current theory and science behind protection and restoration practices, and encouraging a holistic ecosystem approach to managing marine resources. That is why we are adding a new section to our website and quarterly newsletter where anybody can submit their experiences with restoration projects. This may include successes, monitoring techniques, and, most importantly, failed projects. We will disseminate this information through our networks, and also pass it on to the managers of the global database for inclusion there. Please help by looking at the suggested article outline and submitting your coral restoration story today.

Lastly, we would also like to say congratulations to our long-time colleagues and friends who were a part of this project; Ms. Margaux Hein and Mr. Nathan Cook. we are all very proud of the work you guys are doing!

You can view the full paper here.

Coral Fragging Should be Banned

Recently, there has been a great increase in conservation groups participating or dedicating their entire program to coral 'fragging,' or propagation, in order to increase the number of corals on the reef. This has been done with the understanding that they are saving the coral reefs by increasing the abundance of corals, but this practice could be leading to the further decline of the very reefs they are attempting to save. It’s a practice that should be immediately stopped. Programs that fail to understand the genetic implications of their work, and fail to address the multitude of stressors acting upon the reefs will at best be unsuccessful, and at worst contribute to the further decline of coral reefs and the resources they provide.

Coral Spawning and Larval Culturing Program

Coral Spawning and Larval Culturing Programs for Reef Restoration

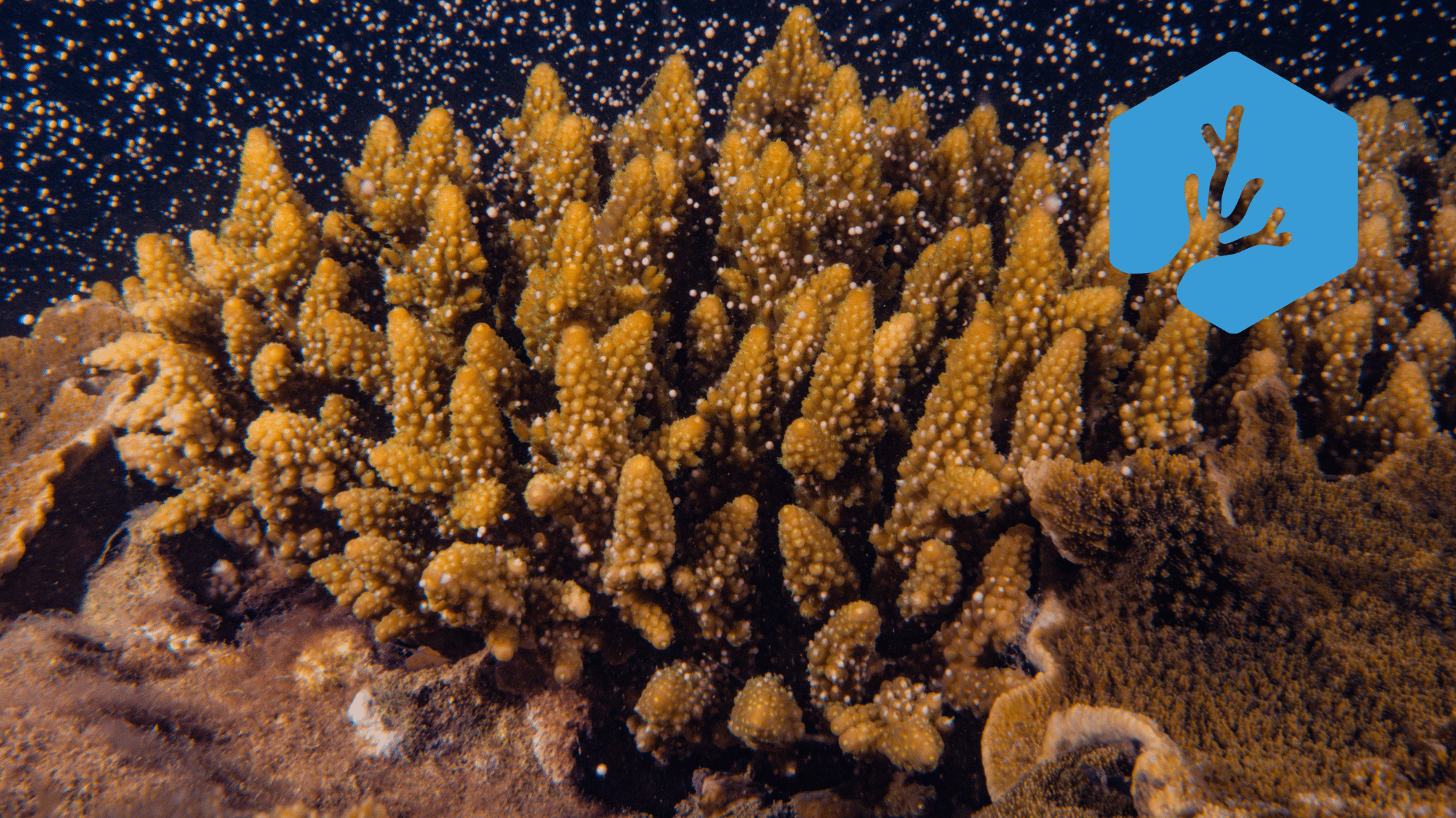

Coral Spawning and larvae culturing is a relatively new form of obtaining feedstock’s for reef restoration. Rather than using ‘donor’ colonies, which are usually sourced from the natural reefs, this technique uses coral eggs and sperm to create new coral colonies which are all genetic individuals. For years this technique has only been available to researchers and professionals with a high amount of knowledge, expertise, and funding. With our improved techniques however anybody can involve in these techniques, improving the genetic diversity of restored areas and increasing the resilience of corals reefs.

Prerequisites

- Be 12 years of age or older

- Be certified as an Advanced diver under a leading diving organization (PADI, SSI, RAID, etc) or an Open Water diver who has satisfactorily completed a buoyancy appraisal with a professional diver

- Demonstrate proper diving ability at an advanced Level and be proficient in buoyancy and self-awareness.

- Be certified in our Coral Restoration Theory & Techniques Course

Standards

- Understand the reproductive cycles of corals and their importance in maintaining diversity and renewing reef growth.

- Understand various modes and evolutionary stable strategies in coral reproduction, and their implications with reef threats and restoration.

- Learn how to track and predict coral spawning events.

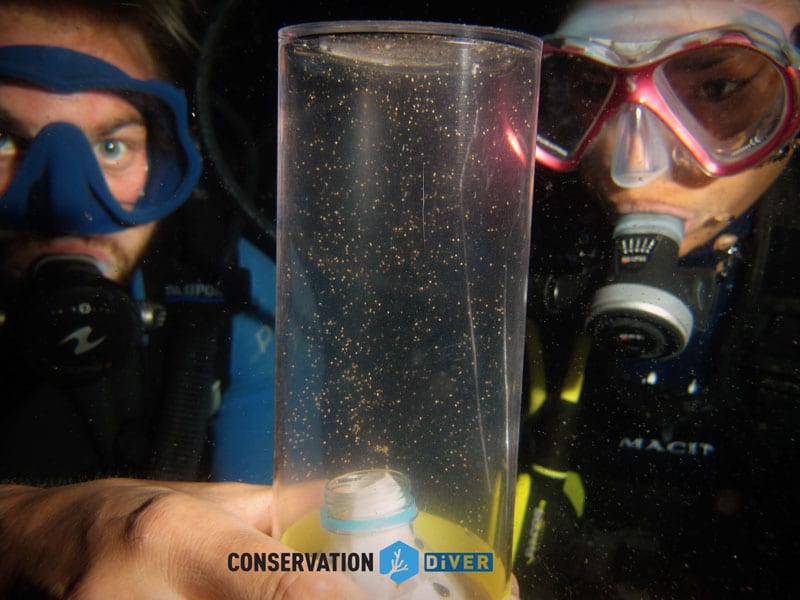

- Learn how to capture coral larvae and eggs and fertilize them with a focus on maximizing genetic diversity.

- Learn how to culture and settle coral larvae using ex-situ husbandry.

- Learn how to maintain and troubleshoot the flow-through larvae rearing ponds.

Requirements

- Attend 3 lectures on coral spawning and larval capturing and culturing

- Perform 3 dives related to coral spawning activities (1) in-water histology and site preparation (2) Spawning observation and timing (3) Larval capture and fertilization

- Assist in the fertilization and rearing of coral larval

Minimum course length 12 hours

Certification Card

Training Centers

Published papers derived from this course:

- Developing community-accessible methods of increasing coral reef resilience through selective coral breeding programs (Chad M. Scott and James D. True)

- Community Based Strategies to Enhance Coral Reef Resilience and Recovery through Selective Coral Larval Culturing to Strengthen Population Genetic Fitness (Chad Scott, Prince of Songkla University)

- Culturing of coral spawn Analysis of the implementation of a scientific project into the community of Koh Tao, Thailand (Christoph Hoppe, Van Hall Larenstein)