Proactive & Reactive Ecosystem Restoration

Proactive and reactive ecosystem restoration are two new terms that more accurately define what is actually happening in the real world. They are replacing the old terms of passive and active ecosystem restoration. The two modes were broadly defined in terms of where the human energy and resources were put in the hopes of bringing back ecosystem health and function.

In passive restoration, the energy was put into stopping the threat and letting the ecosystem recover independently. In active restoration, our energy and resources assisted or facilitated the ecosystem's recovery more directly. These terms were always a bit ambiguous and poorly conveyed the nuance and complexity of the actions being performed by managers.

In a new paper by Hein et al., 2021, the authors discuss this issue and propose using new terms to describe these two restoration branches as they pertain to coral reefs. They introduce the term ‘proactive’ to replace passive, and ‘reactive’ to replace active restoration. These terms more accurately describe the actions being taken and may make communicating the details of these projects more precise and relatable. We at Conservation Diver will be switching up our terminology in support of this, and here is why we think you should too.

Passive and Active Coral Restoration

For decades, the prevailing opinion and policy of reef managers were that protection is always preferred over restoration. By stopping the threats to the ecosystem, the flora and fauna would rebound independently without further human intervention. From this came the term ‘passive restoration,’ meaning that no time, energy or resources were put into the ecosystem to return its health, diversity and function.

However, this term implies that nothing is being done when in fact stopping the threat is anything except “passive.”

For example, Tanote Bay on the island of Koh Tao, Thailand, was one of the more beautiful and vibrant reefs in the entire region. In 2006, the municipal government constructed a large reservoir above the bay to address the island’s unstable freshwater resources.

This was accomplished through massive deforestation, road cutting, and digging on the highest peak in the bay's watershed. By 2008, millions of tons of sand and clay had been washed into the bay, burying the reef under 1-2 meters of sediment. The coral reef was literally gone, and the water quality was extremely poor as more sediment loaded the area with each rain.

In 2008, we worked with the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program, the Save Koh Tao Community Group, and many community volunteers to ‘passively’ restore the bay by stopping erosion and sedimentation.

This included planting hundreds of thousands of Vetiver grass tillers and trees; constructing over a hundred check dams, and installing hundreds of erosion control logs and blankets: all of which took more than three years. In our minds, it was anything except passive, as the word is used in everyday language. However, since we were not working in the coral reef itself, that was how it was defined.

In the same way, the word ‘active restoration’ never really encompassed what managers were doing or moving towards in their techniques and methods. As Hein et al. point out: in the past, restoration was thought of as the act of bringing the ecosystem back to its historical state. However, bringing ecosystems back to their historical state will not be possible in the face of the increased effects of climate change.

Instead, the focus must shift from maintaining historical species to maintaining the “key ecosystem processes, functions, and services through the next few decades of climate change.”

Proactive and Reactive Ecosystem Restoration

The authors (Hein et al., 2021) propose the two new terms as a way to clarify the actions being done and the intent behind them in the context of a rapidly changing planet.

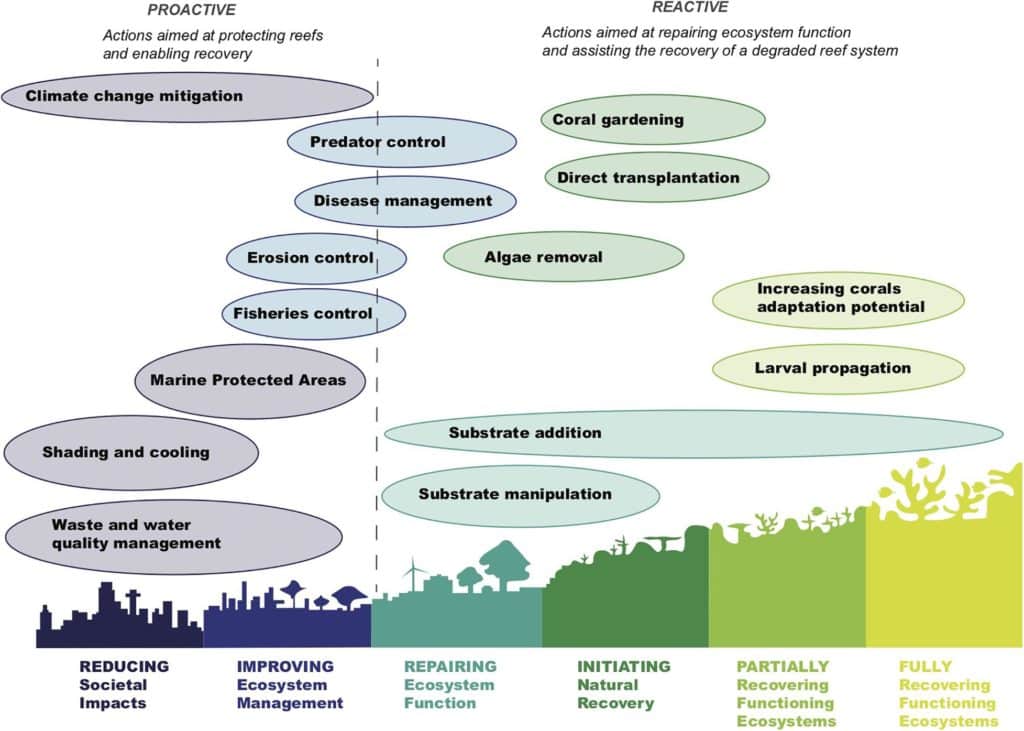

Proactive restoration would thus refer to any act or initiative aimed at “protecting and enabling recovery.” These proactive measures then go on to support the reactive measures “aimed at repairing ecosystem function and assisting the recovery of a degraded reef system, should it not be able to recover on its own.”

With this new, more accurate terminology, the things we do to protect the ecosystem (such as erosion control, wastewater treatment, and mooring buoy installations) are considered proactive measures. These are things done primarily on adjacent ecosystems to help facilitate recovery within the target ecosystem.

In some cases, like when there is still available structure and high larval supply, this can be all that is required to return the ecosystem services and function. And even in situations where those factors are not present, it is still the prerequisite for most successful reactive projects down the line.

Reactive projects in coral restoration would include coral gardening, artificial reefs, larval culturing, and all the other projects reef managers implement as part of a successful holistic program. These are the actions taken to increase the health, abundance, and diversity of key reef species or improve their resilience and help them adapt to changing conditions. The authors of the report developed this graphic to help visualize the actions taken under each mode of coral restoration:

The coral restoration industry is still in its infancy but is one that is becoming more urgently necessary with reefs around the world in rapid decline.

While we work to solve the issues leading to climate change, we must be proactive and reactive in our efforts to preserve ecosystem value and function. These new terms help to show not only the effort and planning that has to go into what was once called passive restoration but also open up what was active restoration to include the work being done to build resilience and assist in the adaptation of corals through breeding programs. This is only one minor point that this vital report brought up, so stay tuned as we dive deeper into its recommendations and implications.

The First Global Coral Restoration Database

"Protection is always preferred over restoration."

That has been the general consensus of the scientific community regarding coral reefs for most of the last five decades. However, in our rapidly changing world, corals reefs are being depleted at an alarming rate, and thus far protective efforts have proven to be insufficient at stopping what could be a global collapse of these important ecosystems. More and more, reef managers have been implementing and developing restoration techniques in what can sometimes only be described as a last-ditch effort to preserve their local resources. There has, however, historically been a major disconnect between their efforts and the work being done by scientists and academics. This is all starting to change with the recent development of the world’s first coral restoration database, as described in a recent publication titled “Coral restoration – A systematic review of current methods, successes, failures and future directions.”

This collaborative effort aims to collect all of the disconnected works being done by universities, NGO’s, local managers, for-profit restoration companies, and individuals around the globe into a cohesive dataset that can be analyzed and used to direct future efforts. This is a major undertaking, especially since there has never been much incentive for reef mangers to publish their work in scientific journals, nor has there been much incentive for for-profit groups and those receiving funding to publish their negative results, or failures. This has led to an incalculable amount of time and resources being wasted as folks attempt to figure things out for themselves, or reinvent the wheel, and often also repeating the same mistakes. In some cases, those working to preserve the environment may also be contributing to its decline.

One of the major problems plaguing coral restoration work can be traced back to a lack of long-term monitoring, which is one of the major criticisms that this paper has brought up. According to the author’s analysis, about 60% of projects reported monitoring for no more than 18 months, with many monitoring for less than one year. However, as anybody in the field knows, pretty much anybody can get corals to grow when conditions are good, but all that work can be for nothing when the next bleaching event or disease outbreak is experienced. So, reports of greater than 70% survival after 1 year may sound great for those projects looking to get more funding, but are they truly restoring the ecosystem?

The authors of the study identified 3 main issues that currently are plaguing the coral restoration industry: “1) a lack of clear and achievable objectives, 2) a lack of appropriate and standardized monitoring and reporting and, 3) poorly designed projects in relation to stated objectives. This new database will hopefully help lead to better understanding and a more focused approach to restoration that actually addresses the issues at hand, and achieves the objectives that have been set out.”

The future potential of the database and the work being done by the project authors can help to legitimize the industry, address the lack of scientific knowledge among some local managers, and help to promote the sharing of new techniques as well as the knowledge on what techniques do not work.

We at Conservation Diver have been attempting to build a network of coral reef managers that are well trained in the current theory and science behind protection and restoration practices, and encouraging a holistic ecosystem approach to managing marine resources. That is why we are adding a new section to our website and quarterly newsletter where anybody can submit their experiences with restoration projects. This may include successes, monitoring techniques, and, most importantly, failed projects. We will disseminate this information through our networks, and also pass it on to the managers of the global database for inclusion there. Please help by looking at the suggested article outline and submitting your coral restoration story today.

Lastly, we would also like to say congratulations to our long-time colleagues and friends who were a part of this project; Ms. Margaux Hein and Mr. Nathan Cook. we are all very proud of the work you guys are doing!

You can view the full paper here.

Coral Fragging Should be Banned

Recently, there has been a great increase in conservation groups participating or dedicating their entire program to coral 'fragging,' or propagation, in order to increase the number of corals on the reef. This has been done with the understanding that they are saving the coral reefs by increasing the abundance of corals, but this practice could be leading to the further decline of the very reefs they are attempting to save. It’s a practice that should be immediately stopped. Programs that fail to understand the genetic implications of their work, and fail to address the multitude of stressors acting upon the reefs will at best be unsuccessful, and at worst contribute to the further decline of coral reefs and the resources they provide.

Coral Restoration Theory & Techniques

Coral Restoration Theory & Techniques

Recent studies have found that about 50% of the world's coral reefs have already been lost, and the other 50% are highly threatened. The long running philosophy of “protection is always preferred over restoration” is a luxury which no longer applies to most regions. More and more, restoration is necessary to preserve the biodiversity and functionality of reefs, and to ensure the sustainability of the resources they provide.

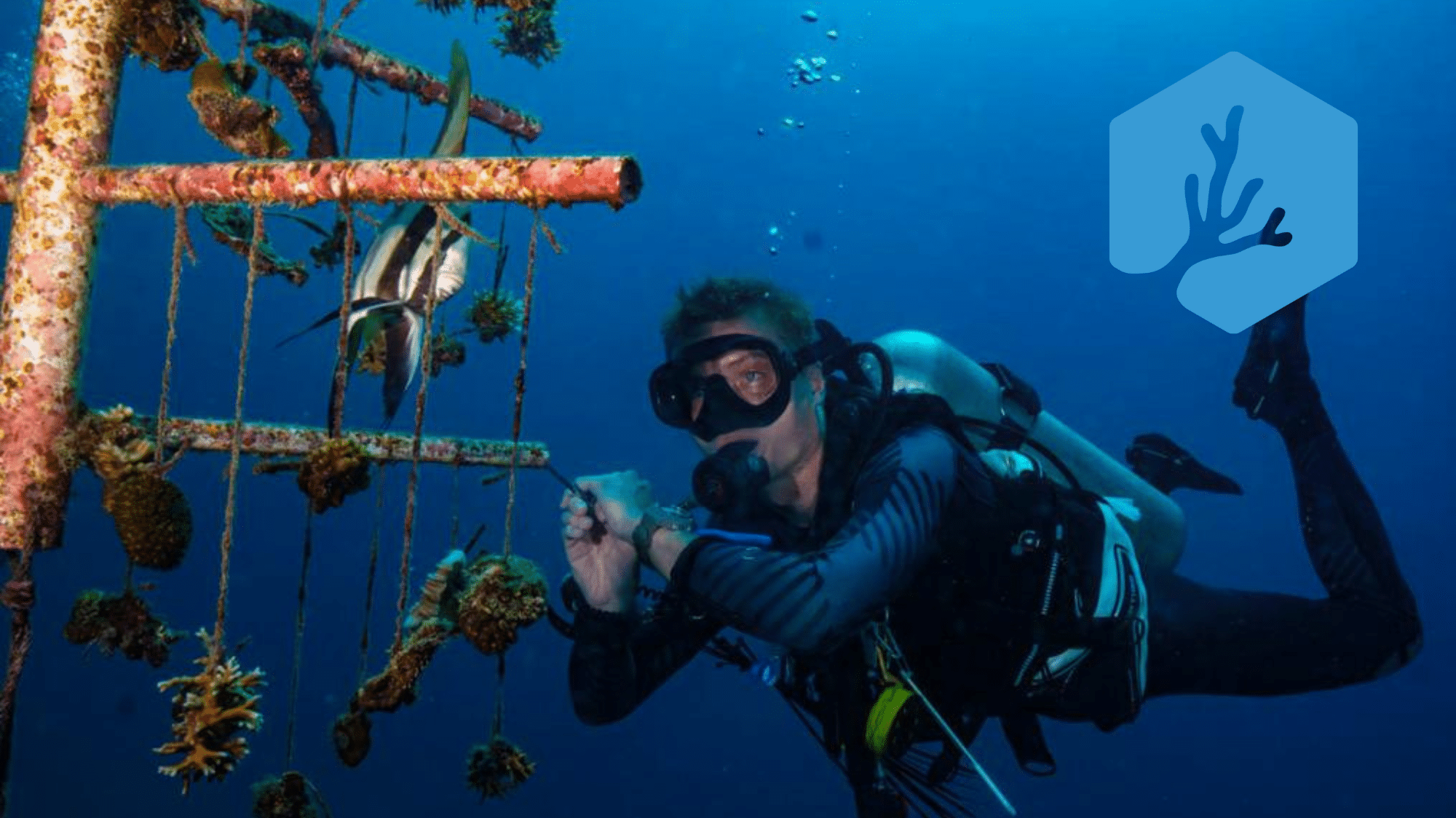

Our reef restoration programs have evolved greatly since our first coral nursery in 2007. We take an ecosystem approach to restoration, which means that we take a holistic approach, focusing on the long-term sustainability and adaptability of the ecosystem rather then just trying to add more corals into areas where they will not survive. This approach has proven successful, as detailed in this 2020 independent analysis of our reef restoration techniques following more than 10 years of our concentrated efforts.

Our courses are on the cutting-edge of science-based coral restoration with a focus on genetics, adaptability, and resilience. We also adhere to the code of ethics as outlined by the Coral Restoration Consortium. Participants in our program will learn all of the theory and techniques behind coral reef restoration, as well as get hands on practice in these techniques. With almost 15 years of experience, we can ensure that everybody coming through our program will leave feeling knowledgeable enough to initiate programs of their own, and confident enough in their skills to carry those projects out to completion.

Our Coral Restoration Topics Include

- Coral Gardening

- Coral Fragment Collections

- Coral Nursery construction, maintenance, and monitoring

- Out-planting corals to the reef

- Monitoring transplanted corals

- Integration of beneficial organisms

- Predator removal

- How to take a genetic-based approach to reef restoration

Prerequisites

- Be 12 years of age or older

- Be certified as an Advanced diver under a leading diving organization (PADI, SSI, RAID, etc) or an Open Water diver who has satisfactorily completed a buoyancy appraisal with a professional diver

- Demonstrate proper diving ability at an advanced Level and be proficient in buoyancy and self-awareness.

- Be certified in the Ecological Monitoring Program

Standards

- Understand the threats to coral reefs, the factors affecting coral growth, and the basics of coral reef restoration

- Understand coral life cycles, the ecological differences between the asexual and sexual reproductive cycles in corals, and the importance of maintaining high biodiversity on the reef.

- Understand the history and evolution of coral restoration techniques as well as local standards (do’s and don’ts)

- Understand the theory behind the use of coral nurseries as well as the practical application of locally and internationally developed techniques

- Perform the practical steps of building and maintaining a coral nursery

- Perform a monitoring dive to take data on the health, growth, and diversity of a coral nursery

Requirements

- Attend the coral nursery knowledge development session

- Perform 2 practical dives either/or: Coral Nurseries - (1) collect coral fragments and secure to the nursery (2) perform maintenance and cleaning (3) collect data on growth rates, mortality, and diversity Coral Gardening - Re-secure at risk coral fragments either wedging or using epoxy or securing to benthic grids

Minimum course duration 12 hours

Certification Card

Training Centers

- Hawai'i - Ocean Alliance Project

- Madagascar - MRCI

- Indonesia – Blue Marlin Conservation

- Thailand – ATMEC

- Thailand – Black Turtle Conservation

- Thailand – NHRCP

Coral Restoration Related Readings

- Coral Restoration E ffectiveness: Multiregional Snapshots of the Long-Term Responses of Coral Assemblages to Restoration

- Ecotourism and Coral Reef Restoration

- Developing community-accessible methods of increasing coral reef resilience through selective coral breeding programs

- Coral restoration: Socio-ecological perspectives of benefits and limitations

- Boat Grounding incident in Chalok Ban Kao, 2015

- Artificial Coral Reefs as a Method of Coral Reef Fish Conservation

- Resilience-based assessment for targeting coral reef management strategies in Koh Tao, Thailand

- Effectiveness of artificial reefs as alternative dive sites to reduce diving pressure on natural coral reefs, a case study of Koh Tao, Thailand